The Maya civilization was one of the most dominant indigenous societies of Mesoamerica (a term used to describe Mexico and Central America before the 16th century Spanish conquest).

The earliest Maya settlements date to around 1800 B.C., or the beginning of what is called the Preclassic or Formative Period. The earliest Maya were agricultural, growing crops such as corn (maize), beans, squash and cassava (manioc). Most famously, the Maya of the southern lowland region reached their peak during the Classic Period of Maya civilization (A.D. 250 to 900), and built the great stone cities and monuments that have fascinated explorers and scholars of the region.

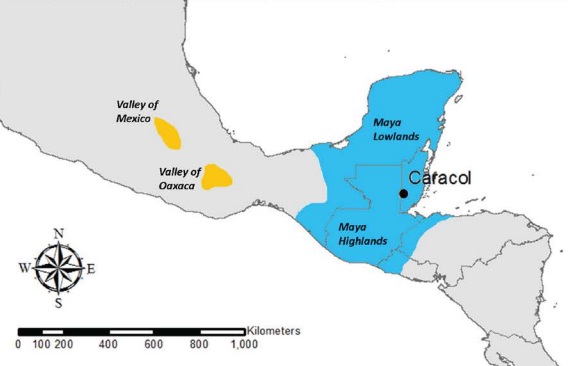

Map of Mesoamerica showing the location of the Valleys of Mexico and Oaxaca in relation to sites in the Maya area

From the late eighth through the end of the ninth century, something unknown happened to shake the Maya civilization to its foundations. The reason for this mysterious decline is unknown, their great cities buried under a layer of rainforest green.

Advances in remote sensing and space-based imaging have led to an increased understanding of past settlements and landscape use, but e until now e the images in tropical regions have not been detailed enough to provide datasets that permitted the computation of digital elevation models for heavily forested and hilly terrain. The application of airborne LiDAR (light detection and ranging) remote sensing provides a detailed raster image that mimics a 3-D view (technically, it is 2.5-D) of a 200 sq km area covering the settlement of Caracol, a long-term occupied (600 BC-A.D. 250e900) Maya archaeological site in Belize, literally “seeing” though gaps in the rainforest canopy.

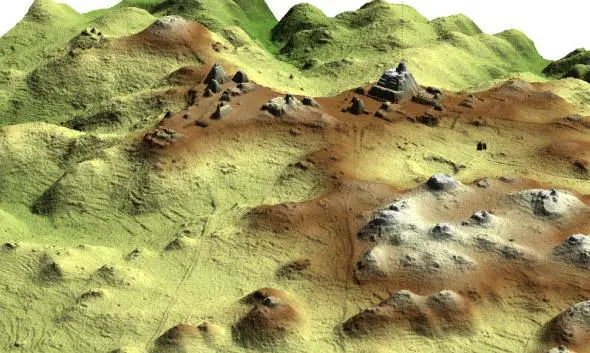

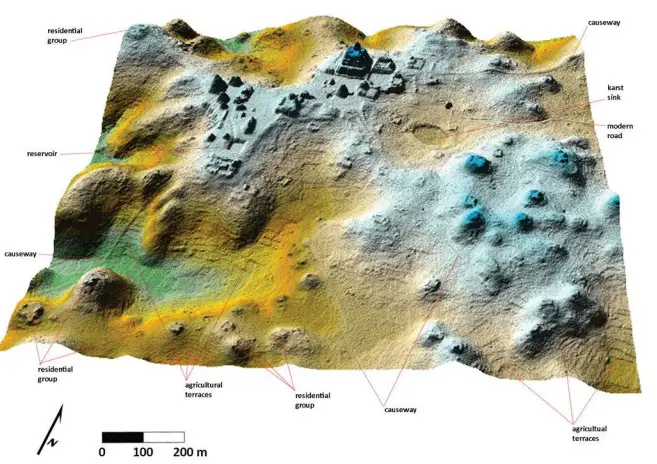

LiDAR 2.5-D image of Caracol epicenter.

Mapping the site of Caracol has been a long and protracted effort that has spanned almost 60 years. By looking at the history of the various mapping efforts at the site, the full potential of airborne LiDAR as a technique for recording ancient Maya sites becomes glaringly evident. The earlier mapping techniques used at Caracol were labor-intensive, tedious, and partial – providing nowhere near the amount of information contained in the digital elevation model gained from LiDAR. Knowledge of pre-LiDAR research is important to contextualize and to fully utilize the results of this new technique. For the last three decades archaeologists all over the world have been using space-based imaging tools to better understand ancient landscape and settlement patterns. Like their colleagues, Maya archaeologists have turned to these techniques to overcome the complications of working beneath a forest canopy—but often with little success. Generally, we have only been able to see archaeological features that extend above the canopy, are in areas devoid of vegetation, or disrupt the forest in a bold way. Even large pyramids can escape the eye in the sky.The success of a large-footprint waveform LiDAR to penetrate the tall complex rainforest canopies of Costa Rica to record ground topography, such as previously unknown hydrological drainage networks (Hofton et al., 2002), suggested that a small-footprint LiDAR might provide the horizontal and vertical resolution needed to detect below-canopy archaeological features.

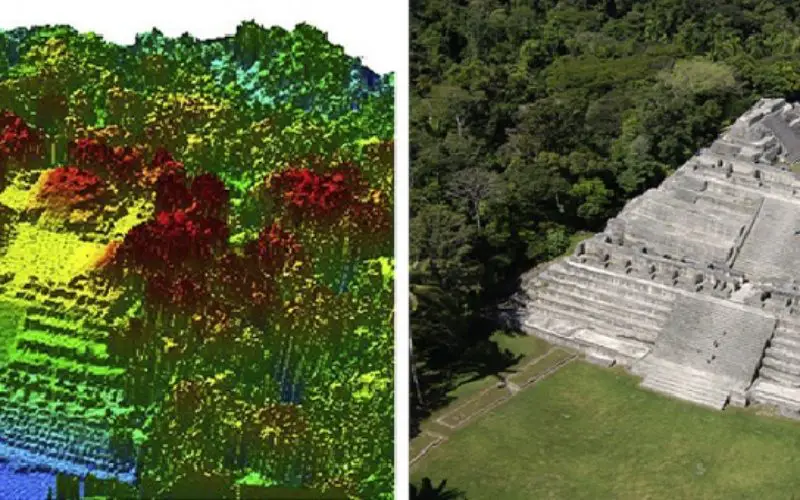

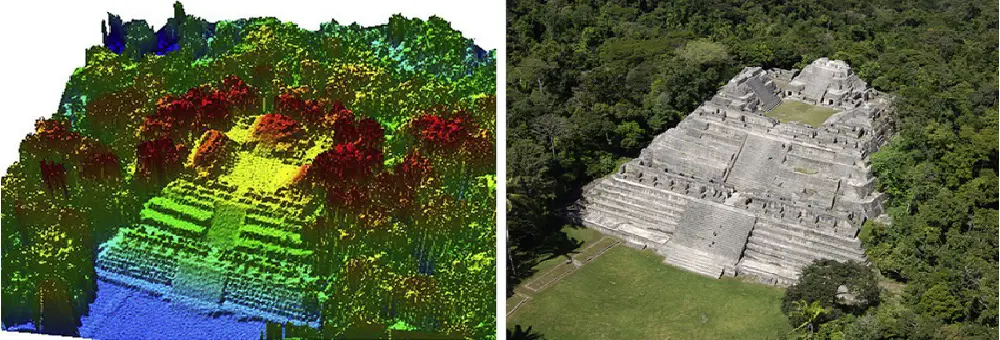

Photograph and LiDAR imagery of “Caana,” Caracol’s main architectural complex; varying colors in the LiDAR data represent different elevations

The result is an accurate, three-dimensional map of both the forest canopy and the ground elevation beneath it. For looking at Maya sites, it was important to take the measurements at the end of the dry season, when the forest is the most depleted. This laser-sensing technology is not by itself new, but has been refined—we used a significantly advanced airborne laser swath mapping (ALSM) system that swept across a 1,500-foot-wide area with each pass of the plane. The Caracol data represent the first time that the ALSM technology has been applied across an extensive region in the Maya area, and the results were stunning.

The LiDAR data confirm that Caracol was a low-density agricultural city encompassing some 70 square miles. The LiDAR images revealed 11 new ones and 5 new causeway termini (concentrations of buildings at the ends of roads), revealing the site’s entire communication and transportation infrastructure at its height during the Late Classic Period (A.D. 550-900). Equally important, the LiDAR images clearly show unmodified hills and valleys at the edges of the surveyed area, indicating the limits of the site and providing hints about why the Maya of Caracol settled where they did and how the city expanded over time.

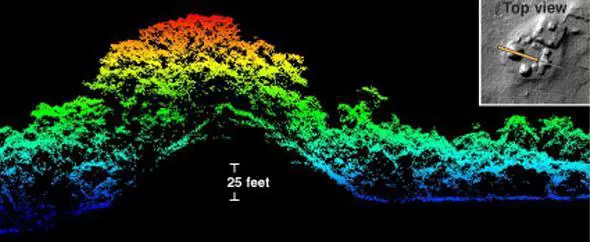

A cross-section through the western mounds of Cahal Pichik at the Maya site of Caracol in Belize (with a corresponding two-dimensional LiDAR image) shows how the LiDAR system can detect both forest canopy structure and the underlying terrain.

On-the-ground confirmation, traditional mapping, and excavation are still necessary to add information about how buildings were used, details, and dating. But because LiDAR covers large areas so efficiently, it could ultimately replace traditional mapping in tropical rainforests, and drive new archaeological research by revealing unusual settlement patterns and identifying new locales for on-the-ground work.

The imaging provided by the Caracol airborne LiDAR data squarely establishes this city as a highly-integrated, large-scale settlement located within an anthropogenic modified landscape. Archaeological investigations can reveal the fine points behind this integration by providing contextual information on dating and function.

2.5 D LiDAR of epicentral portion of Caracol

Further application of LiDAR in the Maya lowlands will add to our understanding of Maya settlement patterns and landscape use, effectively rendering obsolete traditional methods of surveying. This technology will help dispel preconceived notions about the nature and scale of Maya sites by finally permitting the accurate and extensive recording of ancient Maya landscape alteration. LiDAR also has the capability to help researchers identify not only settlement configurations and limits but also potential political boundaries, eventually permitting accurate reconstructions of the size and make-up of ancient Maya states. For now, however, it is enough to be able to see the entire urban landscape for one ancient Maya city. These same data show that the ancient Maya designed and maintained sustainable cities long before such terminology became popularized in present-day development and “green” literature.

References:

– The Use of LiDAR in Understanding the Ancient Maya Landscape