In December 2015, the Mars mission InSight was put on hold, but it has now been provisionally scheduled to launch to the Red Planet at the next opportunity – in May 2018. Technical difficulties with one of the two main experiments – the seismometer – had led to the US space agency, NASA, cancelling the launch that had been planned for March 2016. Now, a decision has been made – the mission has been given a reprieve, and a new launch date in two years’ time. “This is very good news for us,” says Tilman Spohn, Head of the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) Institute of Planetary Research. He is the Principal Investigator for the second key experiment – DLR’s Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3), equipped with a ‘mole’ that is intended to hammer up to five metres into the surface of Mars and measure the internal heat flows of the planet. Spohn continues: “It is the first time that such a measurement is to be carried out, and it will provide us with information on the development of the planet and its heat flow.”

InSight – geophysics on Mars

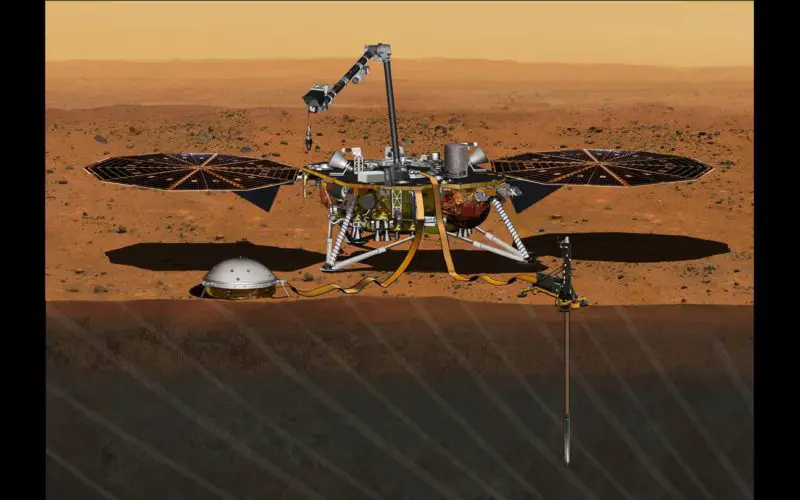

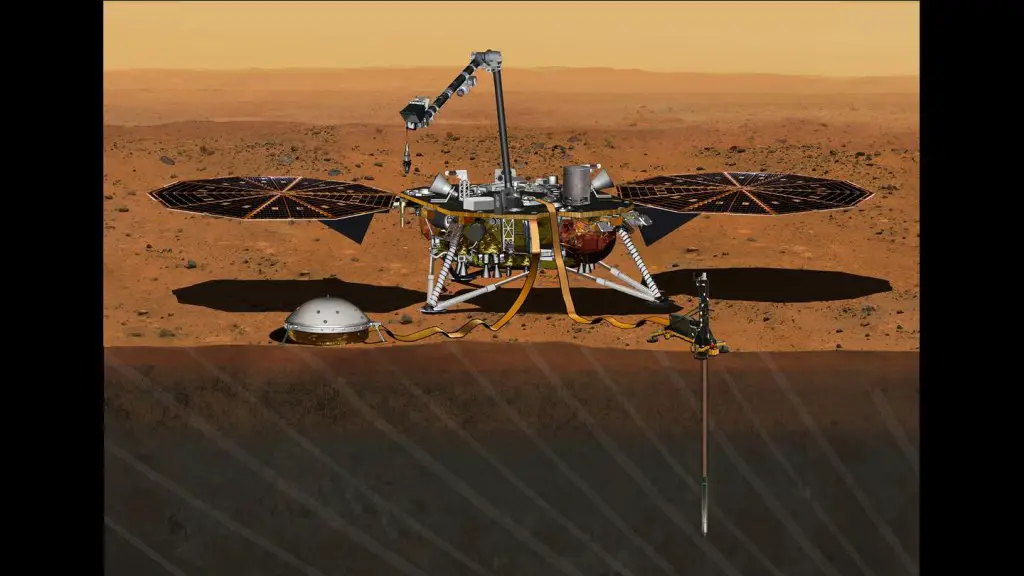

On mars, two instruments are set to research the geophysical properties of the planet. The Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) from DLR in one of these, it will hammer up to five meters into the surface using a ‘mole’ and is intended to measure heat flows inside the planet.

Compulsory time-out for the ‘mole’

The launch is now scheduled for 5 May 2018, and the landing, approximately six months later, on 26 November 2018. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, will redesign, build and conduct qualification testing of the new vacuum enclosure for the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS), the component that failed in December. CNES will lead instrument level integration and test activities. The instrument will be ready by 2017, in time for launch. Due to the delay in the mission, DLR’s planetary researchers are having to transport parts of the sensor package back to Germany, where they will be stored and recalibrated. “However, we much prefer this to a complete cancellation of the mission,” emphasises Spohn. In recent months, the researchers had restlessly been awaiting NASA’s decision regarding the future of the mission. InSight is part of the Discovery programme and is subject to its strict rules; these include a short development timescale, punctual launch and a restricted budget. But, for InSight, NASA has deviated somewhat from these rules. “InSight is an extraordinary mission that is dedicated to geophysical research on Mars,” explains Spohn.

Looking inside the Red Planet

The 2018 experiment on Mars, a fully automated percussion drill, only has one forerunner – the Apollo astronauts used an electric drill to drive bore holes up to three metres below the surface of the Moon. “In principle, these are simple measurements, but they are difficult to execute.” The internal hammering mechanism of the DLR ‘mole’ will drive the sensors into the ground – millimetre by millimetre. This was tested in a metre-high, sand-filled tube at the DLR Institute of Space Systems. A radiometer on the instrument will also determine and monitor the surface temperature at the landing site. The DLR researchers will then be able to derive the planetary heat flow from the acquired surface and underground temperature data. “These findings will give us a greater insight into the development of Earth.” After landing, the DLR instrument will be operated by the Microgravity User Support Center (MUSC) in Cologne.

In addition to the InSight mission, DLR is involved in various other Mars missions. For over 12 years, scientists at the DLR Institute of Planetary Research have been working with a camera on board the Mars Express spacecraft. DLR planetary researchers also offer their expertise during the selection of landing sites for future missions to the Red Planet. The DLR Institute of Aerospace Medicine also has a radiation detector, Radiation Assessment Detector, on the Mars rover Curiosity. On the European Space Agency’s (ESA) ExoMars Mission, scheduled to launch on 14 March 2016, DLR is involved with, among other things, the orbiter’s camera system and is using sensors on the Schiaparelli lander’s protective shield to measure the temperature during entry into the Martian atmosphere.

Source: DLR